The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of four major ligaments of the knee and is critical in providing stability to the knee joint. The ACL is commonly injured during sporting activities but can also be damaged during routine activities of daily living such as a slip or misstep. The primary function of the ACL is to prevent the tibia (shin bone) from sliding out in front of the femur (thigh bone) and provides rotational stability to the knee. You often see health care teams examining athletes on the field when a ligamentous knee injury is suspected with a Lachman test. Injuries to the ACL can range from mild stretching and partial tears to complete ruptures, all of which may influence individualized treatment.

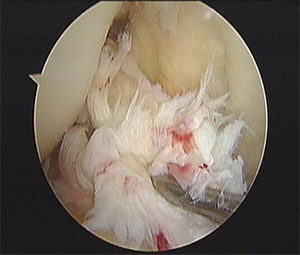

Most ACL tears cannot heal themselves back to the native anatomic position without some type of surgical intervention. The ligament is intra-articular and thus bathed in synovial fluid, which can prevent a clot from stabilizing the healing area. Figure 1 shows an ACL completely torn while Figure 2 shows how the ACL can form into a balled up scar in the front of the knee after a few weeks. When an ACL does try to heal, it often heals in a non-anatomic (and thus loose) position or scars to the posterior cruciate ligament. Partial tears and tears of the proximal portion of the ACL have the best chance to heal non-operatively in a functional state.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2Recently, there has been increased interest in treating ACL tears non-operatively with the Cross Bracing Protocol. In fact, the Washington Post recently highlighted this study. This protocol involves keeping the patient’s knee immobilized in a brace set at 90 degrees or so for a few weeks and then allowing subsequent extension in a gradual fashion. However, this study has several limitations. These limitations include the lack of objective knee laxity testing with a KT-1000 (the testers were not blinded to patient treatment), the lack of second looks with a knee arthroscopy to truly determine if the ACL healed or simply scarred to surrounding tissue, and the lack of randomization of patients to either surgical or non-surgical treatment. The authors are pursuing a more rigorous study to evaluate the Cross Bracing Protocol, and I look forward to seeing these results.

There may be significant downsides of pursuing a non-operative treatment protocol for an ACL tear. One such downside is further damage to meniscus and cartilage. I often see patients who were treated non-operatively for an ACL tear who present with a locked knee with a bucket handle medial meniscal tear. The medial meniscus becomes a secondary stabilizer for anterior translation of the knee once the ACL is torn. However, the meniscus can eventually tear and cause acute pain and inability to extend the knee fully. Furthermore, we often find lesions of the meniscus and cartilage at the time of surgery not easily identifiable on MRI that need to be addressed. In addition, one must account for the time loss if one has continued knee instability after trying a conservative route.

In general, the ACL cannot heal itself without surgery. ACL repair techniques are evolving to preserve the native ACL and heal it with surgery as opposed to reconstructing it. Please see a board certified orthopedic surgeon when discussing ACL tear management. Also, check out our video on ACL prevention.